The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has issued its anticipated recommendations that describe how controllers and processors transferring personal data outside the European Economic Area (EEA) may comply with the ‘Schrems II’ ruling from now on. This is the second blog in our series on the evolving international transfers landscape following the Court of Justice of the European Union [CJEU] decision in July 2020 which ruled the Privacy Shield data transfer mechanism invalid.

In part one of our blog series, “Eight tips for dealing with international data transfers without Privacy Shield”, we introduced the CJEU ruling and looked at its potential impact on transfers post-Schrems II. This blog analyses what you need to know to determine if you can continue sending personal data to third countries, the additional measures that you may need to consider, and the practical steps now required.

What’s new from the EU?

On November 11, the EDPB issued two sets of recommendations following on from the CJEU ruling:

- The European Essential Guarantees Recommendations provides a summary of how to assess the third country which an organisation may send data to, in order to determine if that country’s surveillance measures allowing access to personal data by public authorities are justifiable in line with the EU General Data Protection Regulation [GDPR]

- The Supplementary Measures Recommendations cover the supplementary measures data exporters may need to adopt in order to keep sending data outside of the EEA

The recommendations are subject to consultation and will apply from publication date.

Explaining the Essential Guarantees Recommendations

These recommendations try to clarify whether surveillance laws allowing access to personal data by public authorities in a third country can be regarded as a justifiable interference with the level of data protection the EU guarantees in principle. Therefore, if that country’s legislation complies with the following guarantees, it would offer an essentially equivalent level of protection:

- Processing should be based on clear and precise rules governing the scope and application of the measure in question. For example, there should be a specific purpose to a request from a public authority and requests should have a basis in law

- Demonstrate that the interference with data protection rights is necessary and proportionate with respect to the legitimate objective pursued, for example an objective of safeguarding national security may be deemed more important than combating crime or a law permitting authorities to have general access to electronic communications would be viewed as disproportionate or not necessary

- There should be an independent oversight mechanism in the country (e.g. an administrative body or court)

- The legislation should provide for effective remedies for the data subject; for example, that data subjects’ rights can be enacted, or data subjects should be able to take a legal action before an independent court in the country.

Applying these guidelines in practice will certainly pose a challenge for organisations. Some countries, by virtue of known surveillance laws, will be deemed non-compliant. As we know from the Schrems II ruling, Section 702 of the United States’ Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) infringes on these “essential guarantees”, and so any transfer of personal data that may fall under this will require supplementary measures.

The type of data being processed (e.g. special category), and whether data is transiting through the third country only, are among some of the factors to consider. This should form part of a transfer risk assessment.

Summarising the Supplementary Measures Recommendations

If you have completed the above analysis on the third countries, you should now know if the laws in the third country impact the effectiveness of the transfer mechanisms which you may put in place, such as standard contractual clauses or binding corporate rules (SCCs/BCRs). If they do, you will need extra measures to protect the data.

Technical measures might include:

- Encryption: strong, state-of-the-art encryption in-transit and at-rest. However, this is only effective if the EEA data exporter alone or a trusted third party located in the EEA or an adequate jurisdiction retains the “keys”.

- Pseudonymization: this can serve as an effective supplementary measure as long as it adheres to the requirements around the storage of encryption keys for this purpose

- Split processing: this is where you use two or more independent data importers, located in different jurisdictions, without disclosing any personal data to any of them.

Contractual measures may include:

- Asking the data importer to use specific technical measures such as those listed above

- Provisions to request the data importer to provide the data exporter with reports on any access requests received from public authorities in the third country

- Obligations to review and challenge the legality of any request from public authorities or a local law enforcement authority

- Consider allowing access to the data only with the express or implied consent of the exporter and/or the data subject

- Both parties assisting data subjects in exercising their rights in the non-EEA jurisdiction.

Organisational measures can include:

- Internal policies for governance of transfers (especially with groups of enterprises)

- Documentation of governmental access requests

- Regular publication of transparency reports or summaries regarding governmental access requests.

- Adoption of strict and granular data access and confidentiality policies, based on a strict need-to-know principle, monitored with regular audits and enforced through disciplinary measures

- Involvement of the data protection officer on all international data transfer matters

- Adoption of strict and state-of-the art data security and data privacy policies.

Ultimately, the data exporter/importer has to ensure that any measures it takes are effective. It may need to combine several measures. The challenge for an organisation is that the guidelines state that sending EU data which can be viewed “in the clear” by a recipient in a third country is not permitted. This leaves companies that have, for example, a global customer support model or a corporate Human Resources system with multi-country access, potentially having to halt these transfers or implement alternative solutions.

So what should I do now?

- Conduct a review of your transfers and determine the status of the third country

- If the third country is not seen as essentially equivalent, then review the three categories of measures to understand which ones apply to you

- This can be done in a transfer risk assessment

- Implement the findings of your risk assessment and ensure you have documented the process

- Carry out a regular review of all international transfers.

Final word … for now

The guidelines are welcome and provide the next steps which all organisations have been waiting for. Organisations will face difficult questions where they have multi country data processing “in the clear” where the required supplementary measures could not be applied in current business models. The road ahead is still far from clear.

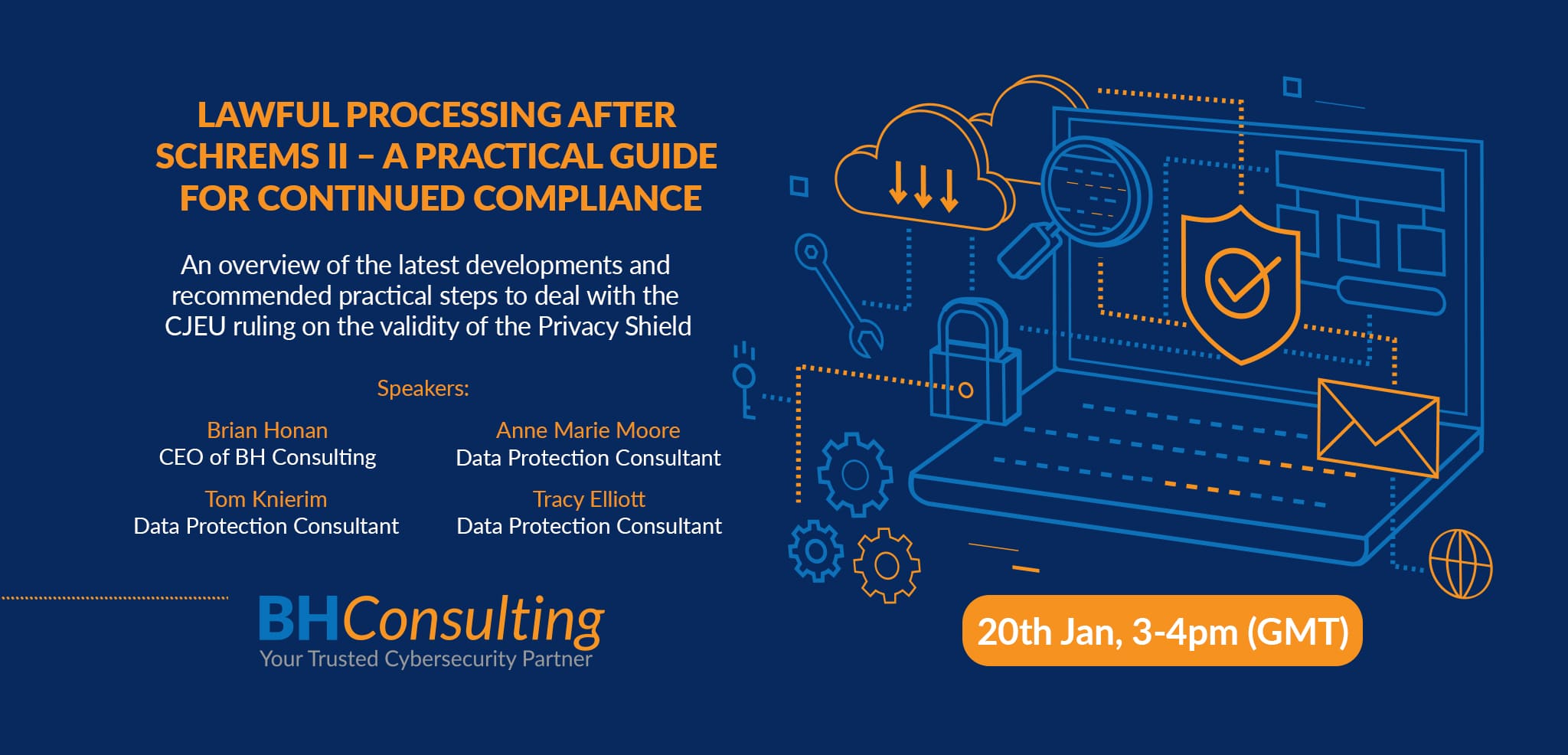

On Wednesday 20 January, you can join BH Consulting’s team as they talk through this issue in a webinar, “Lawful processing after Schrems II”. The virtual panel session will feature data protection specialists and cybersecurity experts looking at this issue and how businesses affected by it can respond. To register, visit the event page.

And stay tuned…

The final blog in our series will explain the new standard contractual clauses and how to implement them.